Thinking in Tongues:

How Multilingualism Can Preserve

Cognitive Function in Aging Adults

Reading Time: 6 Minutes

Date Published: 1/18/2026

Author: Hans Manish

Artist: Elgin Tawiah

Thinking in Tongues: How Multilingualism Can Preserve Cognitive Function in Aging Adults

Introduction

Over the past decades, life expectancy has experienced a rapid increase from 69 years in 1960 to almost 80 years by 20101. In short, our population continues to age, and the neurobiological effects of aging grow increasingly pronounced worldwide. Geriatric cognitive decline is becoming much more prominent, in developing countries, as the older population2 grows, accompanied by losses in executive function, memory, and learning ability. Many of these reductions in cognitive ability correlate with neurogerontological diseases (i.e., neurological conditions affecting older populations as a result of age-related changes to the brain), such as Alzheimer’s disease, Vascular dementia, and Lewy body dementia. As our population encounters these conditions and symptoms, preventive measures to protect cognitive function with age become increasingly crucial. Recent studies link multilingualism as a major potential pathway to achieve this.

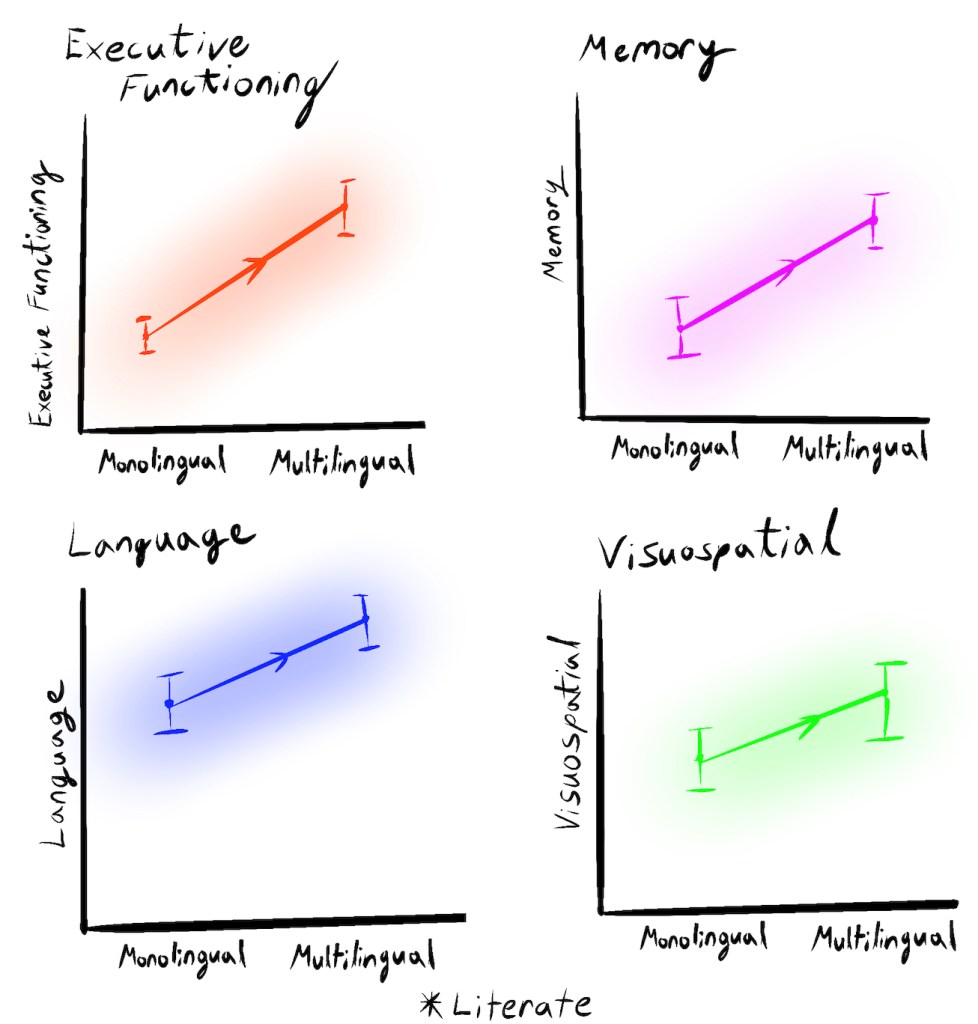

The development of speaking fluency in two or more languages, serves a critical role in preventing the cognitive decline associated with aging. Specifically, multilingual people display higher reserve (i.e., preservation of cognitive performance despite aging4), executive function, and memory4,7. Especially given that many neurogerontological conditions correlate with deficiencies in these domains, developing strength in these abilities through multilingualism represents a valuable strategy for combating the cognitive decline that can accompany aging.

Improved Reserve

One of the strongest connections between multilingualism and cognitive ability lies in the demonstrated improvement in reserve6, particularly brain reserve and cognitive reserve. Brain reserve refers to the ability of our brains to prevent the physiological deterioration of neurons and neural connections associated with aging or brain damage. Cognitive reserve refers to the ability to maintain cognitive function through flexible, highly neural networks.

Reserve, as a whole, consists of a variety of factors, including genetics, education, physical environment, social interactions, and physical activity4. However, in general, reserve accumulation begins in youth, continues throughout adulthood, but buffers cognitive function in older age. In terms of multilingualism, reserve scores significantly higher in youth who grew up multilingual than in youth who grew up monolingual. As such, multilingualism offers a pathway for developing both physiological and cognitive protections against neural deterioration.

Executive Function

Multilingualism also plays a role in bolstering general executive function, the ability for our brains to make decisions, control voluntary activities, and predict outcomes to achieve a certain goal5. Multilingualism encourages these characteristics because it requires the brain to choose the appropriate language for the situation and to speak it. Speaking in multiple languages requires conscious effort to prevent sudden language switches, to interpret contextual cues for proper language usage, and to prevent cross-language interference3, the impact one language produces on the comprehension and acquisition of another. This process becomes especially apparent during language learning and acquisition because practicing language use requires strict attention to the target language, the language being learned, thereby reinforcing these skills.

In addition, multilingualism improves executive function by harnessing linguistic competition as a method of language control3. In essence, the competing neural networks that activate when speaking one language instead of another develop executive function that activates one network while suppressing the other. This improves executive function when completing other decision-making and selection tasks, with downstream effects on more complex, goal-oriented tasks. These developments prove integral to preserving cognitive function over time since the ability to complete complex cognitive tasks deteriorates first, making multilingualism crucial for preserving these skills.

Memory Formation and Recall

These linguistic experiences significantly improve memory function in the adult brain, including improvements of episodic memory (memory of event details), semantic memory (memory of data or facts), and working memory (temporary storage of new information and retrieved memories)4. Building on these cognitive skills, memory strengthens through increased grey matter volume and neuronal density in the basal ganglia, which coordinates motor learning, motor selection, and provides structural support to the hippocampus. Grey matter volume and density also increase in the hippocampus, which stores both episodic and semantic memory. White matter density, which represents connections between brain regions, also increases in these areas, bolstering communication between brain areas and strengthening neural networks.

Degrees of Multilingualism

Greater multilingual engagement correlates with increased executive function and enhanced neural indicators of cognitive performance, demonstrating that multilingualism influences cognitive outcomes to different degrees3. The number of languages known, for example, increases cognitive skill in these domains (though studies note that quantifiable differences with each improvement decrease with each additional language). Therefore, while learning multiple languages improves cognitive abilities, the increase that accompanies each language decreases after the second language.

Additionally, linguistic distance (i.e., the difference in languages between their syntactic, structural, phonological, and morphological characteristics) contributes to these cognitive domains5. For instance, bilingualism in languages with greater linguistic distance displays increased reserve and executive function than bilingualism in languages with lower linguistic distance. Considering these two aspects, gaining fluency in multiple, dissimilar languages maximizes the potential of multilingualism to improve cognitive function,

Impacts on Neurodegenerative Diseases

Although far from a cure, multilingualism carries the potential to completely transform the way we approach preventative health in the field of neurogerontology. Many neurodegenerative diseases associated with aging face symptoms that can be alleviated through improvements in reserve, executive function, and memory linked to multilingualism2. Alzheimer’s disease, for example, correlates with memory loss or a lack of memory consolidation. Vascular dementia, among other forms of dementia, originates from neurophysiological degeneration that can be prevented by multilingualism. Of course, multilingualism is far from a cure for these detrimental diseases. However, by encouraging multilingualism throughout education from a young age, society works towards developing cognitive strength through language learning, creating an incredible impact throughout the aging process.

Conclusion

As our population grows increasingly older, neurogerontological conditions become far more prominent in our population, associated with reductions in cognitive ability and deteriorating neurological health. Multilingualism, however, offers a possible preventive measure, enhancing cognitive abilities across three domains: reserve, executive function, and memory. These abilities improve largely through direct physiological strengthening in the brain, both in the basal ganglia and in the hippocampus. Neural bolstering increases with the number of languages known and their respective linguistic distances. Ultimately, multilingualism provides a valuable tool in preventing neurodegenerative diseases present in aging populations.

References

- Brown GC. Living too long. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(2):137-141. doi:10.15252/embr.201439518

- Cao Q, Tan CC, Xu W, et al. The prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;73(3):1157-1166. doi:10.3233/JAD-191092

- Elin K, Gallo F, Gabrielsen A, Voits T, Rothman J, DeLuca V. Flanking age: multilingualism and its role in shaping cognitive decline and neural dynamics. Neuroimage. 2025;317:121312. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2025.121312

- Gallo F, Myachykov A, Abutalebi J, et al. Bilingualism, sleep, and cognition: an integrative view and open research questions. Brain Lang. 2025;260:105507. doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2024.105507

- Gallo F, Myachykov A, et al. Linguistic distance dynamically modulates the effects of bilingualism on executive performance in aging. Bilingualism. Published online November 3, 2023. doi:10.1017/S1366728923000743

- Stern Y, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Bartrés-Faz D, et al. Whitepaper: defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(9):1305-1311. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.219

- Strangmann IM, Briceño E, Petrosyan S, et al. The association between multilingualism and cognitive function among literate and illiterate older adults with low education in India. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Behavior & Socioeconomics of Aging. 2025;1(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bsa3.70018