The Shrinking Brain

Reading Time: 5 Minutes

Date Published: 11/22/2025

Author: Isabelle Chen

Artist: Elgin Tawiah

Introduction

As we age, our bodies undergo several physical changes that become indicators of aging. For example, your hair begins to turn grey, there are more visible wrinkles on your face, your muscles are not as strong as they were before, etc. However, what people do not realize is that while your body is undergoing all these physical changes, it also undergoes internal changes that are a result of aging. Specifically, your brain begins to shrink1.

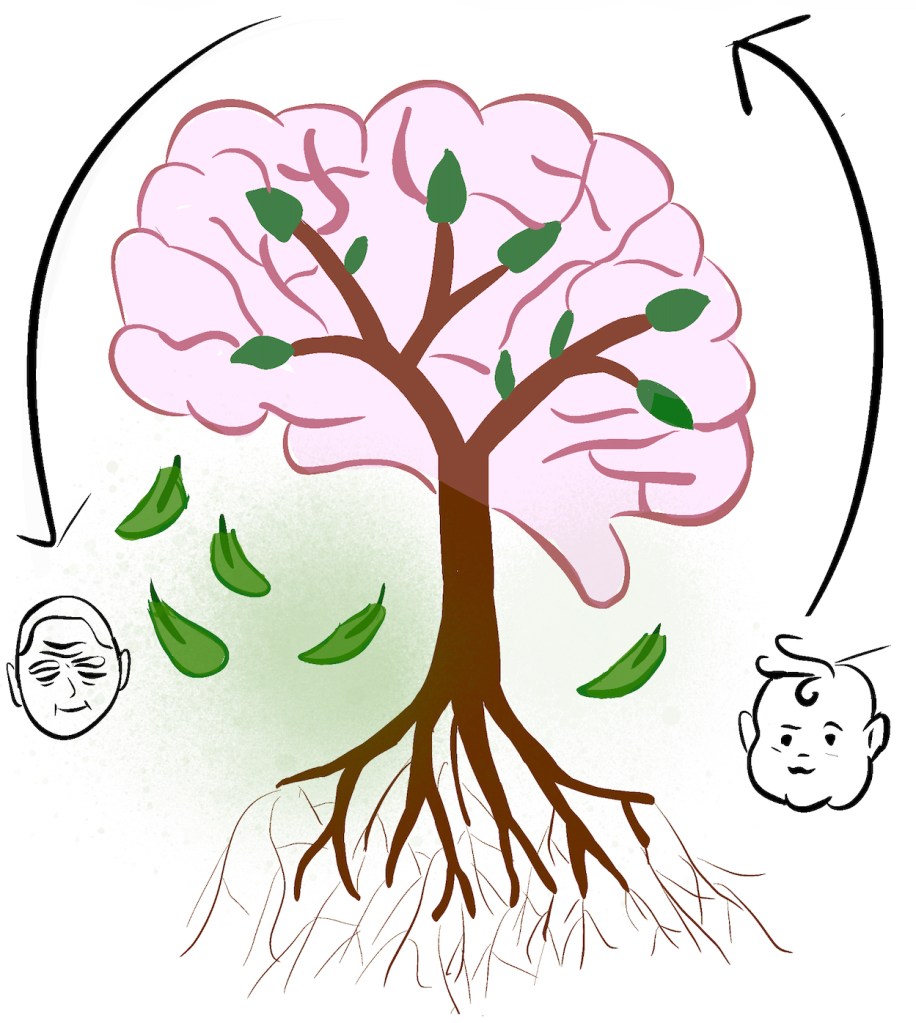

Our brains are not fully developed until age 25; however, once you reach your 30s and 40s, parts of your brain begin to lose volume1,2,3. The exact reasons and details for why our brains undergo this loss are still unclear, yet the brain’s deterioration increases even more by age 601,2,3. While there are a few negative effects of our brain losing density, like everything else, it is a natural process of aging2,4.

What parts of the brain shrink?

Our brains lose volume because the neurons themselves begin to shrink and retract their dendrites as the brain ages2,5. While not every part of the brain undergoes a loss of mass, some research has shown that the specific areas that lose volume could be related to the sex of the individual since sex hormones have been shown to affect cognitive processes in adulthood3,6.

Women in particular are prone to hormonal changes as they age, especially around menopause, when large fluctuations in hormone levels lead to a sharp and lasting decline in sex hormones. These hormonal imbalances may partly explain the higher incidence of Alzheimer’s found in women compared to men3 and a greater age-related hippocampal and parietal lobe volume loss6. While hormones may play a role in which regions of the brain are more susceptible, aging also follows a broader pattern that affects certain areas more than others.

Not all parts of the brain experience the same amount of change. The main parts of the brain that shrink are the hippocampus and frontal lobe, specifically the prefrontal cortex1,2,3,4,5. These parts of the brain are the last to mature during adolescence, but they are also the first to exhibit age-related shrinking2,3,4,5. These two regions contain important nerve fibers that relay information throughout the whole body, and because the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex support memory and executive function, shrinkage in these areas decreases synaptic connections2,4.

The result of these region-selective changes due to age is an overall decline in brain volume. After the age of 40, the overall brain volume declines to around 5%3 per decade, and this rate of decline may increase with age, especially after the age of 701,2,3,5.

How does it affect us?

Because the brain has a lower density, there will be fewer connections and synapses between neurons and the neurotransmitters that lead to slower cognitive processing1,2,3,5. Therefore, older people might experience decreased attention, decreased ability to multitask, and slight memory loss, especially their episodic and semantic memory1,4,5. This could mean that people might have more difficulty remembering basic information that they once knew or recalling old memories.

Part of the reason connectivity decreases is due to changes at the cellular level, where neurons can no longer maintain optimal protein quality. Brains typically maintain a state of proteostasis, which ensures that high-quality proteins are made correctly and at the right time7. Nevertheless, when this cycle slows down, neurons end up with unfinished proteins that clump together, slowing down cognition7. Constant disruption in protein balance can cause a loss of energy and potential damage if they are accumulated over time7.

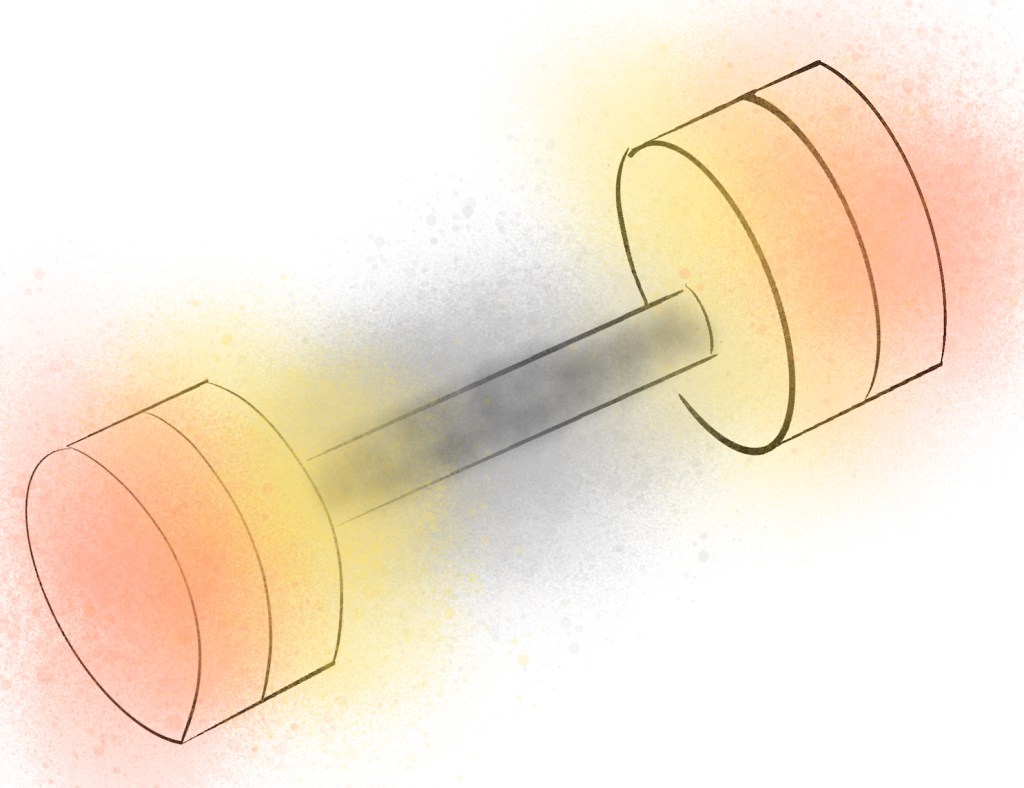

In addition to changes in grey matter, aging also affects changes in white matter, which plays an important role in communication between different regions in the brain. This is a result of myelin sheath, a protective coating around axons that enables faster signal transmission, gradually degenerating1,3,5,8. This deterioration impairs processing speed and reduces cognitive function1,3,5. Since white matter consists of bundles of myelinated axons8, any loss of myelin directly impacts communication between different brain regions, effectively contributing to the overall decline in neuronal processing and executive functioning1,3,5.

Some of the regions white matter helps to connect are the brain’s emotion center in the limbic system. Therefore, a decreased density in white matter also results in a decline in dopamine and serotonin levels. It has been shown that dopamine levels decrease around 10% per decade, which leads to worsening cognitive and motor performance3,5. Another explanation for the decrease in dopamine levels could be that the dopaminergic pathways between the frontal cortex and striatum decline or that levels of dopamine itself simply decline with increasing age, which leads to a reduction in binding between receptors3. Unfortunately, once the brain begins to shrink, there is an increased risk of strokes, dementia, and white matter lesions3.

While normal brain aging is different from neurodegenerative diseases, these same age-related shrinkages can increase the vulnerability to conditions such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and dementia. Many diseases, such as these, include more accelerated and widespread versions of the loss of synaptic connections, hormonal and neurotransmitter imbalances, and other deficiencies2,3,5.The Society for Neuroscience also notes that changes in neuronal morphology, as a result of aging, could reduce the brain’s reliance against additional stressors (i.e., oxidative stress, alcohol and drug intake, poor sleep quality, etc.). It is clear from these results that the combination of aging with additional stressors may increase the proclivity to neurodegenerative diseases; however, this does not make disease inevitable as a result of aging.

Despite these changes in decline, older brains have also proven to demonstrate strength. For instance, many older adults have maintained a larger vocabulary and a deeper understanding of the meaning of words4,5. It is a testament to the brain’s robust capacity to preserve or even enhance5 function in certain domains in the face of age-related changes.

Preventative Measures

Even though it is natural for the brain to shrink with age, there are ways to slow down the process. A lot of the ways to reduce brain aging are also ways to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease2,3. Lower cardiovascular risk may be linked with lower biological age, meaning that individuals who exhibit strong cardiovascular health often display biological attributes found in youth in spite of their chronological age3.

Regular exercise, maintaining a healthy diet, and low to moderate alcohol intake are key factors to supporting a healthy cardiovascular health3. Ensuring proper exercise can increase executive functioning and reduce aging in white and grey tissue density3. Since consumption of alcohol is associated with hippocampal shrinkage, minimizing intake, or possibly even abstaining from it, may aid in maintaining the hippocampus’ structural integrity and functioning3.

Another key factor that is often overlooked, but is just as crucial as diet and exercise, is mental stimulation. Keeping the brain active through reading, playing an instrument, picking up a new hobby, or even simply socializing can strengthen neural circuits and build that long-term cognitive resilience2,5. Prioritizing mental stimulation alongside cardiovascular health can help a long way in slowing down the brain’s aging process.

Conclusion

Just like the rest of the human body, the brain goes through an aging process that results in parts of the brain beginning to shrink. Despite a few methods that might slow down the aging process, our brains naturally begin deteriorating as time goes on, yet this does not necessarily lead to diseases like Alzheimer’s and dementia.

However, it is worth acknowledging that there are many limitations to studies relating to the aging brain since there tends to be a small sample size3. Because most of these studies are cross-sectional, they fail to capture the inherently complex nature of aging and its variability across different individuals in different cultures, lifestyles, and environments.

Nevertheless, even though our brains shrink with age, they keep their structural integrity and functional resilience2,4,5. This remarkable feature is what suggests the brain was not merely an organ to survive but an organ built to integrate experience and insight beyond decades.

- Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Changes That Occur to the Aging Brain: What Happens When We Get Older. Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. Published June 10, 2021. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/changes-occur-aging-brain-what-happens-when-we-get-older

- Felson, S. (Ed.). (2025). Which Area of the Brain Is Most Susceptible to Shrinkage as We Age? WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/healthy-aging/which-area-of-the-brain-is-most-suscepitble-to-shrinkage-as-we-age

- Peters R. Ageing and the Brain. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2006;82(964):84-88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2005.036665

- National Institute of Aging. How the Aging Brain Affects Thinking. National Institute on Aging. Published 2023. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/brain-health/how-aging-brain-affects-thinking

- Society for Neuroscience. How the Brain Changes With Age. BrainFacts.org. Published August 30, 2019. Accessed November 21, 2025. https://www.sfn.org/sitecore/content/home/brainfacts2/thinking-sensing-and-behaving/aging/2019/how-the-brain-changes-with-age-083019

- Small SA, Rabinowitz D, Fedorova I, et al. A longitudinal study of hippocampal volume in healthy adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(4):390-398. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040038007

- Hipp MS, Kasturi P, Hartl FU. The Proteostasis Network and Its Decline in Ageing. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2019;20(7):421-435. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-019-0101-y

- Campellone J, ed. White matter of the brain: Medlineplus medical encyclopedia. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002344.htm. Published 2016.