Altered Mitochondrial

Trafficking

and Its Contribution to

Neurodegenerative Disease

Reading Time: 8 Minutes

Date Published: 10/27/2025

Author: Augustus Clarke

Artist: Elgin Tawiah

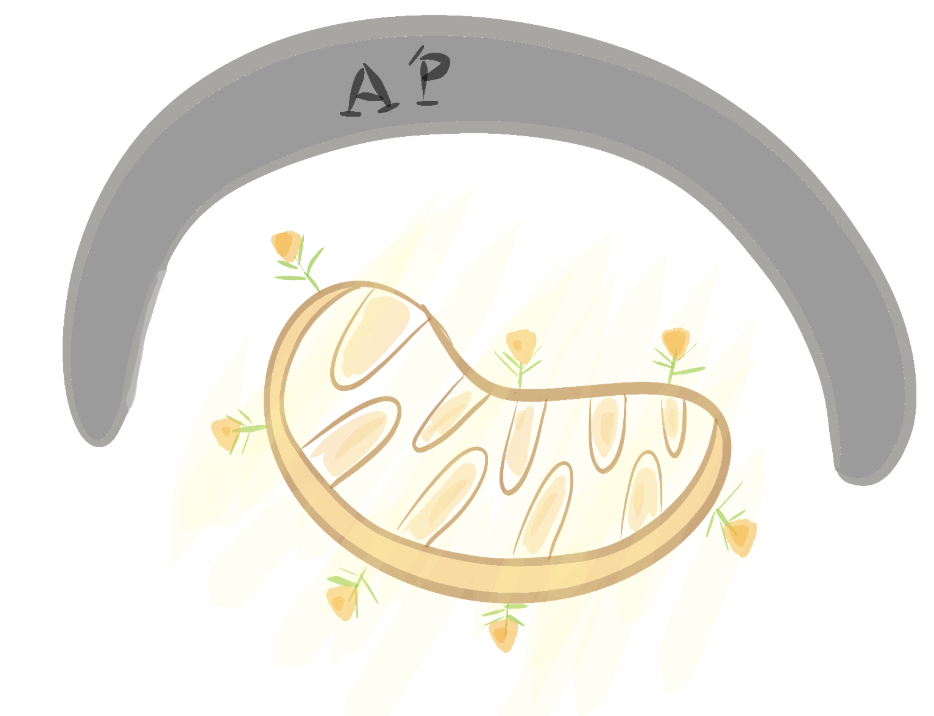

The organization of neural circuits has been studied since the amazing work of Camillo Golgi and Franz Nissl, whose techniques of staining have provided the foundation for modern neuroscience. These discoveries revealed the complex structure of neurons within the brain, which helps us understand how intracellular organelles support neuronal function. Among these organelles, mitochondria play a large role in how neurons function. Casually known as “the powerhouse of the cell”, they supply ATP to help with cellular processes, regulate calcium to maintain signaling balance, and regulate apoptosis (a form of programmed cell death)1. Neurons are highly polarized cells with long axons and synaptic connections; they depend on precise mitochondrial trafficking to deliver energy where it is needed most, like synapses and growth cones2. When these processes are disrupted, it is recognized as a key factor in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases1,2. This article reviews the mechanisms of mitochondrial trafficking in healthy neurons, the alterations observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD), and the therapeutic implications of targeting these pathways.

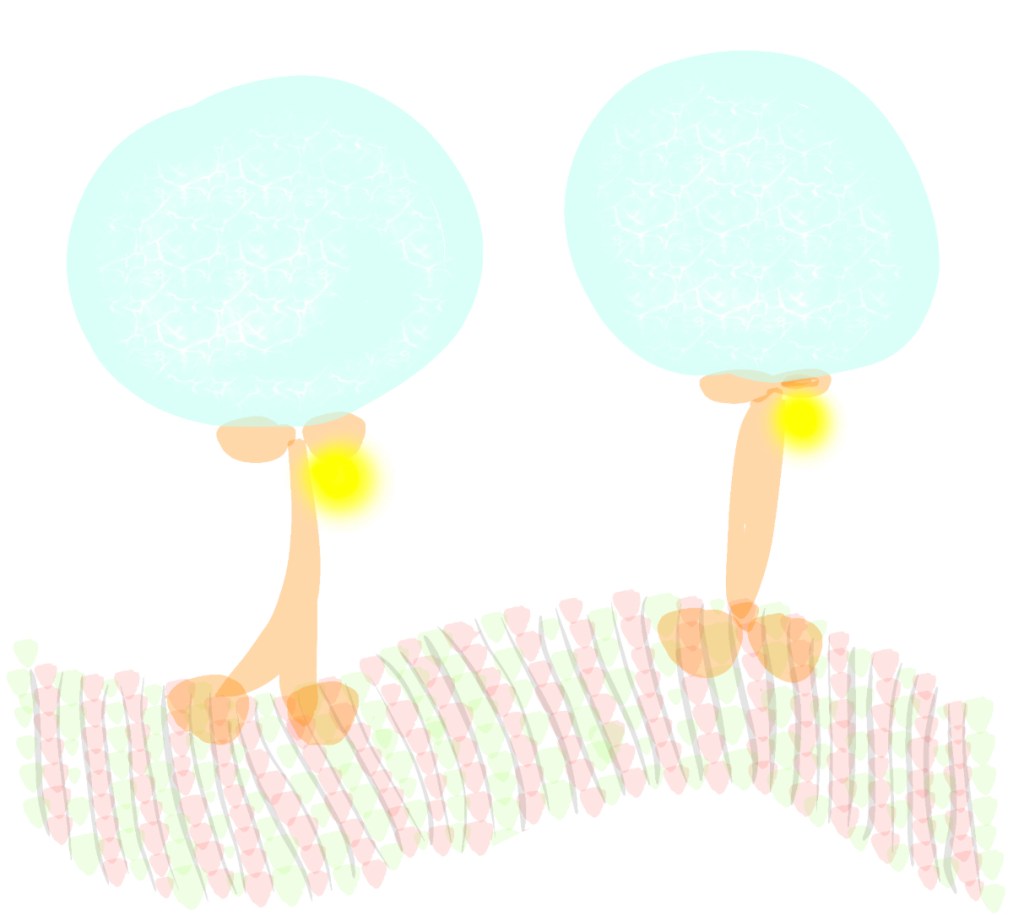

In healthy neurons, mitochondrial transport is needed to keep neurons alive and synapses functioning2,4. Mitochondrial transport in dendrites and axons is bidirectional and comprises numerous interactions between motor proteins using microtubules, adaptor proteins, and regulatory signaling pathways2. Kinesin mainly controls anterograde transport, which moves mitochondria into axon terminals and synapses, allowing high-energy demands at each site to be met2. Retrograde transport is controlled by dynein, which returns old mitochondria to the soma for degradation2.

Calcium-sensitive adaptor proteins like Miro, which bind to TRAK proteins to allow for proper docking and motility, strongly control this process2. Elevated levels of calcium within activated synapses cause mitochondria to pause their activity, which creates a high metabolic demand and need for neurotransmission2. The functions of mitochondrial trafficking extend beyond mere transport. At the synaptic terminal, mitochondria provide the energy needed for neurotransmitter release and vesicle recycling. During synaptic activity, mitochondria control calcium influx, which is necessary to prevent excitotoxicity (a process where neurons are damaged or killed by excessive activation of glutamate receptors) and neuronal death4. Also, mitochondrial positioning is critical for developmental processes, such as axonal pathfinding and growth cone motility, and for mature neuronal plasticity, the brain’s ability to change and adapt in response to different situations2,3. So, proper distribution and transport of mitochondria are needed for sustaining both structural and functional aspects of neurons2,4.

The importance of mitochondrial trafficking becomes apparent when examining its cause in neurodegenerative diseases. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), both amyloid-β plaques, extracellular deposits of misfolded protein that toxically accumulate in the brain during AD, and hyperphosphorylated tau, an abnormally modified version of tau protein that impairs neuronal function, contribute to defects in trafficking5. Amyloid-β disrupts the function of Miro and TRAK complexes, while tau destabilizes the microtubule network that is needed for efficient transport5. This results in reduced mitochondrial movement toward synapses, leading to ATP deficits and impaired calcium buffering2,5. This synaptic dysfunction appears early in disease progression and may cause detectable cognitive decline, which highlights the potential role of trafficking defects as an initiating factor in AD pathogenesis5. In Parkinson’s disease, mitochondrial dysfunction has long been recognized as a definite cause1,6. Mutations in PINK1 and Parkin, genes that code for proteins classically associated with mitophagy (the cellular process of selectively degrading and recycling damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria), also impair mitochondrial movement.

Neurons start malfunctioning due to chronic oxidative stress caused by the damaged mitochondria during the failure of their degradation enhancement transport processes in the axon1,6. Another feature of Parkinson’s pathology is the accumulation of alpha-synuclein, a protein that under standard conditions controls synaptic vesicle transport and neurotransmitter release, also worsens the situation by hindering axonal transport, and the deficiency of mitochondria becomes more pervasive. Since the substantia nigra’s dopaminergic neurons’ long, highly branched axons depend on effective mitochondrial transport to maintain neurotransmission, these trafficking failures seem to be related to the neurons’ selective vulnerability1,2,6.

Another example of altered trafficking is Huntington’s disease. The pathogenic huntingtin (Htt) protein mutant with the enlarged polyglutamine tract interferes with the communication between the mitochondria and the motor or scaffold proteins that move along microtubules. The resulting slowing of mitochondria, especially in distal axons, causes a localized energy deficit and disruption of calcium signaling. These changes are closely associated with axonal degeneration, one of the primary causes of the pathology of Huntington’s disease. All of these findings across AD, PD, and HD suggest that trafficking defects in neurodegeneration are universal1,2. The discovery that many neurodegenerative diseases are primarily caused by defects in mitochondrial trafficking has spurred research into possible treatment approaches. Targeting the trafficking proteins themselves is one promising strategy. Restoring appropriate motility and distribution may be facilitated by stabilizing interactions between motor proteins and mitochondria or by improving the activity of the Miro and TRAK complexes2,5. Enhancing mitochondrial quality control is the focus of another approach. Stress on neuronal circuits would be reduced by promoting mitophagy and other clearance processes, which would stop the accumulation of immobile and dysfunctional mitochondria6. Additionally, pharmacological interventions are being studied. Gene therapies, peptides, and small molecules are being developed to alter trafficking pathways or make up for their malfunction1,2. Drugs that improve mitochondrial dynamics, for example, may encourage both fusion and fission processes, thereby indirectly promoting healthier distribution. At the same time, animal models have demonstrated the advantages of lifestyle changes like exercise and calorie restriction. These non-pharmacological techniques seem to enhance mitochondrial transport and dynamics7, providing a possible adjunct to more direct molecular treatments. Neuronal survival and function depend on mitochondrial trafficking, which makes sure that calcium buffering and energy supply are precisely matched to the needs of neural circuit8. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases are all characterized by disruption of this process, where compromised transport leads to synaptic failure, axonal degeneration, and neuronal loss7. In addition to expanding our understanding of neurobiology, an understanding of the mechanisms governing mitochondrial motility also creates opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Restoring mitochondrial distribution is a great future strategy for slowing the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. One of the ongoing challenges is turning these basic discoveries into clinically effective treatments that can stop or decrease the damage brought on by neurodegeneration1,2.

- Klemmensen MM, Borrowman SH, Pearce CA, Pyles B, Chandra B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2023;21(1):e00292-e00292. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurot.2023.10.002

- Sheng ZH, Cai Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13(2):77-93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3156

- Hedges V. Visualizing Cells of the Nervous System. openbookslibmsuedu. Published online December 15, 2022. https://openbooks.lib.msu.edu/introneuroscience1/chapter/visualizing-cells-of-the-nervous-system/

- Vos M. Synaptic mitochondria in synaptic transmission and organization of vesicle pools in health and disease. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience. 2010;2. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00139

- Quntanilla RA, Tapia-Monsalves C. The role of mitochondrial impairment on Alzheimer´s disease neurodegeneration: the Tau connection. Current Neuropharmacology. 2020;18. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159×18666200525020259

- Mitophagy and Parkinson’s disease: The PINK1–parkin link. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Cell Research. 2011;1813(4):623-633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.08.007

- Johri A, Beal MF. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2012;342(3):619-630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.112.192138

- Whitley BN, Engelhart EA, Hoppins S. Mitochondrial dynamics and their potential as a therapeutic target. Mitochondrion. 2019;49:269-283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2019.06.002