The Truth Behind Intelligence: Are We Born With It, Can We Change It – And If So, When Do We Peak?

Reading Time: 26 Minutes

Date Published: 08/31/2025

Authors: Jeffery Batres and Elgin Tawiah

Artist: Elgin Tawiah

Amid a devastating plague that struck Europe in the 14th century, scientific innovation stagnated as universities shut their doors. In The Black Death, historian Philip Ziegler described the conditions:

“Mortality among men of learning had been calamitously high. Four of Europe’s thirty universities vanished in the middle of the fourteenth century: no one can be sure that the Black Death was responsible, but it would be over-cautious to deny that it must have played a part.” 1

Over three centuries later, another plague struck: the Great Plague of London in 1665. Despite these conditions, in a manor at Woolsthorpe, Isaac Newton was not deterred.2 He closed his doors and began to write. In his notebook, he recorded observations of the behavior of falling objects. From these, Newton derived mathematical equations that explained the force of gravity.3 Naturally, his groundwork in foundational physics led him to lay the framework for differential equations and integral calculus. Despite his immense contributions to science, Newton was also fascinated by lenses and their ability to magnify objects. This interest led Newton to study the effects of light on lenses and prisms, culminating in the observation of chromatic aberration, the inability of light to focus all colors to a single point.4

Newton did it all in 18 months.5

In this short span of time, referred to as the annus mirabilis (miraculous year), Newton performed the majority of his theoretical and experimental work.6 At the time, he was twenty-three years old. Then, in his forties, Newton published his famous Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy).7 Being revered as the “Titan of Science,” Newton truly lived up to the name. For his time, Newton’s discoveries were extraordinary. Not only did Isaac Newton transcend centuries of scientific knowledge, but he also transformed the contemporary understanding of the Earth and the universe. Newton’s robust quantitative and predictive framework provided better explanations for decades of theoretical and speculative foundations that preceded his time.

Proceeding Newton, at just twenty-six years old, Einstein had performed experimental work to support his famous theories of relativity and the photoelectric effect.8

At the age of eight, Mozart composed his first symphony, Symphony No. 1 in E flat, K. 16. By the age of seventeen, Mozart had composed a total of eighteen symphonies.9

Unsuspectingly, there are exceptions to this trend of intellectual prowess at a young age. For instance, Harry Bernstein published his first book, The Invisible Wall: A Love Story, at the age of 96. However, Bernstein didn’t stop there; he would go on to publish three more major books between the ages of 96 and 100, solidifying his intellectual tenacity.10

Among all of these figures lies a common pattern. Each one displayed some form of intelligence, but each also differed in age. As a matter of fact, the age gap extends well over 50 years between Mozart and Bernstein. We have all been fascinated by intelligence, so it comes as no surprise that achieving it at an early age or later in life seems attractive. Such curiosity brings us to question if there is an age at which we reach our “intellectual prime”? Pondering that idea raises more questions: Is the ability to process more volume of information negatively correlated with age? Is the age of our “intellectual prime” the same for everyone? Do society, culture, and generations influence when it happens? What even is intelligence? And why does any of this matter? Scholars for generations from different fields, such as neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy, have dedicated decades of study to better understand human behavior and development.

What is Intellectual Prime?

Intellectual prime is a curious concept that can be loosely defined as the period in someone’s life when they develop cognitive abilities, such as problem solving, reasoning, memory, perception, and creativity (among other abilities), at their highest level, relative to a population, that result in peak mental capabilities and innovations. This is the most common term we find ourselves familiar with. Examples of these figures include the ones mentioned above: Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, and Mozart, among others.

However, this definition itself depends on the perspective it’s viewed from. For instance, intellectual prime itself can also be used to describe a person who is currently at their intellectual peak, not relative to a population. To better visualize this, an example would be a journalist writing at the peak of their life, where they can think clearly, learn quickly, and produce new ideas rapidly compared to other points in their life.

In another sense, intellectual prime may be defined more abstractly. Take, for example, Plato’s dualistic theory of Forms. Plato envisioned the world as not a reality but a fragment of reality.11 Where did the true piece of reality come from? According to Plato, reality was transcendent, and bodies of ideality lay in a more idealistic plane. Our bodies and souls (i.e., our values and human characteristics) lie in this realm; meanwhile, our physical bodies lie in the physical realm. In the abstract plane, intellectual prime was the purest form of intelligence a human could wish to achieve.

Because of the various forms intelligence manifests, we shall analyze the different premises of intelligence. From these premises will stem the answer to when our prime intelligence peaks.

Neurological Basis of Intelligence

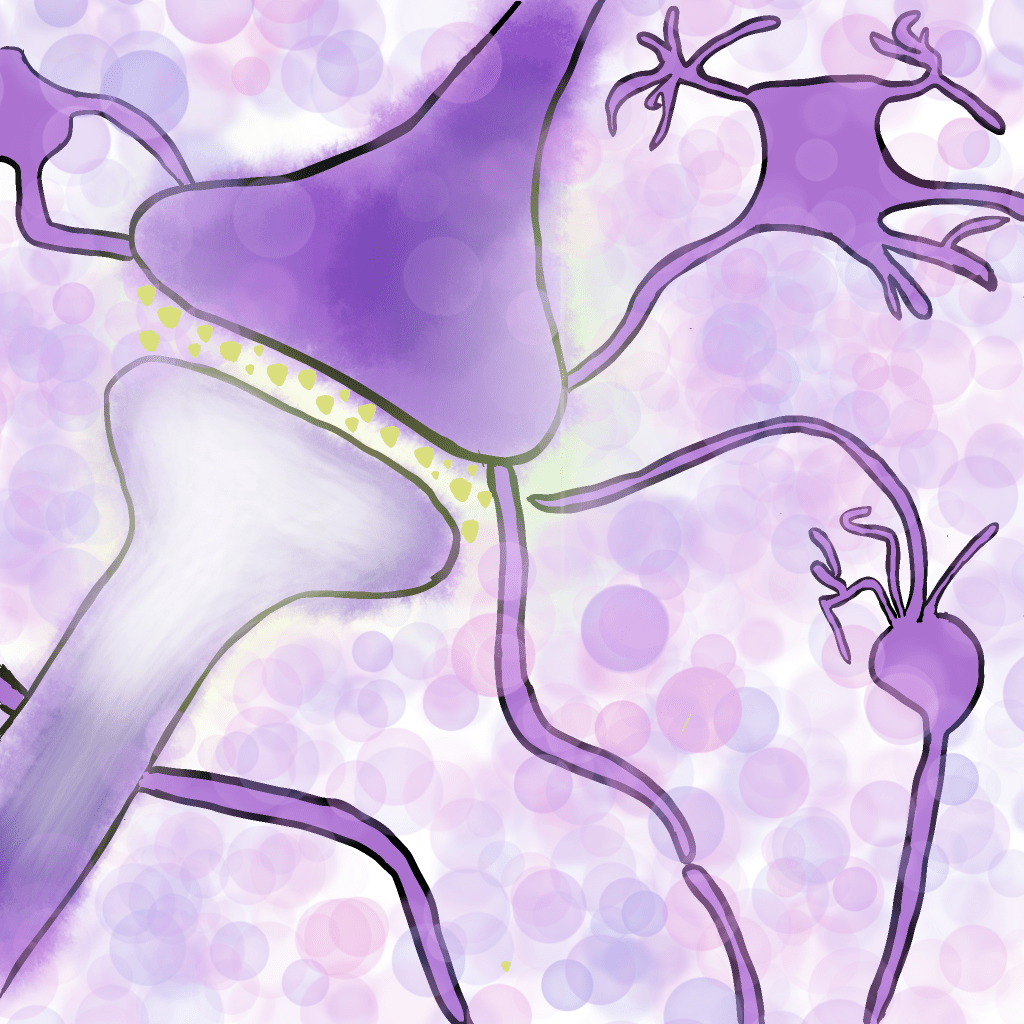

Since birth, the brain undergoes the process of neurogenesis, the birth of new neurons. These new neurons then form synapses, which exchange chemical and electrical signals throughout the brain, giving rise to higher-order functions like cognition and motion. However, neurogenesis does not occur at an indefinite rate. Synaptic density peaks within the first year of life.12 Afterwards, the brain undergoes synaptic pruning, a process that removes “weaker” or infrequently used synapses; as a result, human aging is associated with a decrease in synaptic density.13 Synaptic pruning is especially prevalent after the adolescent stages of life.14

Alterations to pruning can result in serious neurodevelopmental consequences. In Schizophrenia, excessive synaptic pruning leads to impaired neural circuitry. Similarly, Alzheimer’s disease involves excessive synaptic pruning directed by microglia,15 key cells of the brain that act like immune cells. In contrast, Autism is associated with less synaptic pruning, indicative of the heightened sensitivity.16 However, despite the tendency for synapses to decrease with age, synaptic pruning is vital for making the brain more efficient by preserving only the most important connections, neuroplasticity. The neurological basis of intelligence therefore is convoluted and must be broken up by age, factoring in several considerations and the interplay of thousands of genes.

By compiling 123,984 patient MRI scans from over 100 primary studies,17 researchers were able to reach the following conclusion: Grey matter volume peaks around the age of six years old. From these studies, significant conclusions can be drawn. Grey matter, located on the outside surface of the mammalian brain, contains the cell bodies of neurons and dendrites, which are similar to antennas that receive chemical and electrical signals from synapses, are located and are responsible for processing higher-order processes in mammals. It is unsurprising that higher grey matter volume is associated with increased mental development and increased cognition, implying a greater capacity for learning, memory, reasoning, decision-making, etc. However, it is important to note that grey matter density increases until about the age of twenty.18 After early adulthood, grey matter begins to decline,19 a gradual process that has been associated with cognitive decline due to decreased dendritic arborization, forming of new dendritic connections and therefore synapses.

In contrast, white matter, comprised of myelinated axons that connect neurons, volume peaks between late 20s to early 40s.17 Myelination helps enhance the speed at which axons communicate information in the brain. Increases in white matter enhance signal conduction and allow for higher cognitive function. However, after thirty, myelin sheaths begin to degrade, slowing signal transduction.17 This occurs since the oligodendrocytes, cells that myelinate the axons, become less efficient. Furthermore, white matter decline, especially after the age of fifty,17 leads to the appearance of white matter intensities, which is a common finding across MRI scans. White matter intensities are bright spots of white matter that are indicative of dementia, strokes, cognitive decline, etc.

Subcortical volume peaks during mid-adolescence.17 Subcortical regions, which lie underneath the brain cortex, including the basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum. These regions control movement, memory, hormones, senses, and emotion. However, the volumetric decline of Subcortical regions is subject to variability. Some brain regions decline faster than others, with no clear indication as to which brain region declines the fastest.17 Although Subcortical volume decreases after adolescence,17 these results are less significant as decreases in Subcortical volume are indicative of increased efficiency in the brain rather than a reduction in higher-order processes that interpret information coming from these brain regions.

Lastly, ventricular volume does not peak but rather gradually increases over time.17 In this case, ventricular volume reached an apex at the age of a hundred since participants used in these studies ranged from zero to one hundred.17 Increases in ventricular volume are linked to atrophy or neuronal loss. As the ventricles expand, tissue that was once present in that area loses its space.

While these trends provide key information in interpreting how the brain changes over time through aging, a trend can not fully encapsulate all the complexities behind intelligence, so long as the brain is plastic and can form new or more efficient connections. The brain undergoes a constant tradeoff of size and efficiency. Adults and children ultimately have different ways of processing and storing information. There is no correct way.

Psychological Basis of Intelligence

It’s undeniable that neuroscience has a lot to say about intelligence; however, intelligence doesn’t stop there. Intelligence lies in the real world, where it manifests through our behaviors and actions. The framework of intelligence shifts to thinking of what it really means to be intelligent.

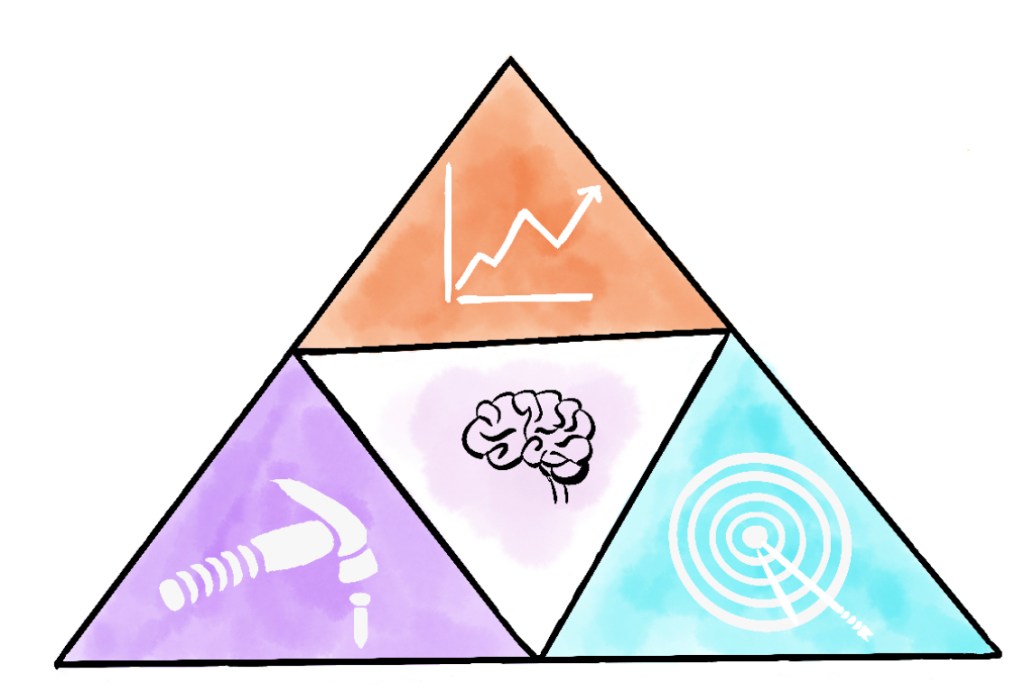

One such notable shift in intelligence was the introduction of the g factor, otherwise known as the general intelligence factor. Charles Spearman, an emerging psychologist at the time, was responsible for this theory, known as the general factor theory or the two-factor theory.20 Upon analyzing the results of the academic scores of students, Charles Spearman noticed a pattern among the test-takers: the test-takers with the highest scores also tended to do well in other areas.20 After statistical analysis, Spearman concluded that this newfound pattern resulted from a strong link between someone’s intellectual capacity and their ability to perform certain tasks.20 Essentially, Spearman summed up his discovery with the introduction of his g factor, a quantifiable attribute that explains why some individuals tend to perform better across different tasks. However, if this were the case, how would you explain the discrepancies in the other individuals who didn’t perform well overall performed better than those who did at certain tasks? To help understand this discrepancy, Spearman also developed an s factor (hence, the two-factor theory), another metric used to explain specialized intelligence in certain areas. In addition, the g factor contributes to the s factor. On one hand, the g-factor helped explain a broader intelligence that encompassed people (e.g., if one person is good at one subject, then they are likely to be good at another because their g factor is high), and, on the other hand, you have the s factor, which helps explain certain skills people excel in.

Similar to Spearman’s idea of a general factor of intelligence, Lewis Terman refined Alfred Binet’s discovery of the IQ to the IQ that determines a person’s overall intelligence. The intelligence quotient, or the IQ, was originally intended to evaluate which children required more academic assistance.20 However, Lewis Terman took it one step further, and used this IQ definition to generalize to a bigger population. As a result, through some refinement in today’s standards, the IQ tests a person’s logical-mathematical and verbal reasoning. It is these abilities that determine a person’s general intelligence to the population where they took the test. Terman’s ideas even went as far as attempting to prove that gifted individuals (i.e., individuals with IQs greater than 130) are physically, financially, and socially superior to other individuals in a longitudinal study.21 He found gifted individuals to be better off financially, physically, and socially.21

Even though Spearman and Terman had statistical data to point to such correlations, other psychologists found his explanation quite bothersome. For example, Howard Gardner believed that oversimplifying human intelligence to a mere factor or two was an overstatement.22 Unlike Spearman, Gardner believed intelligence spanned across 8 categories: linguistic, logistical/mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalist. For instance, in Frames of The Mind (1983), Gardner describes a patient who suffered a brain injury on the left side and lost linguistic abilities, but he retained his musical abilities and could still conduct and compose music. Apart from deriving the theory of Multiple Intelligences, Gardner established a basis for these intelligences with distinct requisites to classify a category of intelligence.20

Robert Sternberg also believed intelligence not to be the result of one factor, but he also believed stretching intelligence too thinly to be inadequate. He believed intelligence to be broken into three categories: practical, creative, and analytical. This gave rise to his Triarchic Theory. A practical intelligence describes the intelligence found in an IQ test; creative intelligence describes the artistic components of an individual, as well as innovation; and analytical intelligence describes what is known as “street smarts.” 20

While some of these theories are backed up by statistical rationale as well as logical rationale, these do not come without critiques. Spearman’s theory narrowly defines intelligence as the result of one factor. Alfred Binet’s original scope was small and did not intend for solid predictive intelligence of the individual. Terman’s scope was also highly specialized and capitalized on the idea of eugenic theory, where the superior are those who are smarter. Gardner lacked empirical data (e.g., it’s hard to test for intrapersonal intelligence) and broadened his scope to the point where others might argue that some of his categories are mere skills. Sternberg, while seemingly practical, also lacked empirical data (e.g., it’s hard to test for creative intelligence).

Can intelligence be improved?

Intelligence should not be viewed as a static concept but rather a dynamic process. As discussed previously, the brain is constantly changing to break weak connections and form new ones.

However, it is important to address the belief that intelligence is determined from birth. Although it has been difficult for researchers to pinpoint specific genes that contribute more to intelligence than others, a wide variety of genes can be inherited that contribute to intelligence.23 In fact, researchers have identified over 538 genes in the human brain that contribute to intelligence.23 To name a few, LINC01104, PDE1C, FOXO3, EXOC4, SNAP25, Intergenic, ATXN2L, and APBA genes facilitate brain development and neural communication in the brain. However, these genes are found in nearly every human.24 In rare cases, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, mutations may occur in one gene that may impact brain development.25 Pinpointing individual genes in the human brain and determining their rarity and significance is not an effective way of assessing intelligence, as the brain is like a roadmap with thousands of pinpoints. The ineffectiveness of one location will, in most cases, not be the sole determiner for intelligence.25 For the average human, genetic variation will not be the sole determining factor for intelligence.25 But what about Mozart? While some have speculated this could help explain child prodigies, current studies26 have not identified specific genetic pathways responsible for extraordinary early-age capabilities. However, these studies have not identified specific pathways that may be linked to extraordinary capabilities at a young age.26 An indirect measure of intelligence, the IQ test attributes 50% to 80% of variation due to genetics.23

In most cases, intelligence is determined and can be improved based on environmental factors.27 Environmental factors that influence intelligence include lifestyle and activities.

Several research studies relate diet and exercise to intelligence 28, 29, 30 The brain, being the complex organ that it is, uses 20% of the energy derived from food. The main source of energy to the brain comes from sugar.31 Variation in glucose intake, therefore, has an impact on the brain. When individuals go on prolonged or extreme diets, the brain instead uses lactate or ketone bodies for energy.31 On the other hand, foods with high glycemic indices, a measure of how quickly food raises blood sugar, have an impact on short-term memory due to large fluctuations in blood sugar.32 Low iron consumption can lead to motor and cognitive impairments in children.33 Low iron status in older children affects neural morphology, myelination, and synaptogenesis.33 Higher levels of carotenoids, present in leafy vegetables, such as Lutein, are associated with higher cognitive scores.34 Lutein has also been associated with improved speed of temporal processing in young adults.34 Protein intake is critical for brain development. A lack of protein intake is associated with a decrease in protein phosphorylation, decreased brain volume, and altered hippocampal formation.35 It is therefore no surprise that supplementing malnourished children with protein led to an improvement in cognitive performance,36 and Omega-3 intake is positively associated with relational memory.37 Besides dietary changes, exercise is a crucial component of intelligence. Aerobic fitness is directly correlated with cognition and brain structure.38 In a study,39 children who engaged in less fitness activity had decreased inhibitory control and a smaller dorsal striatum, which controls procedural memory. Furthermore, the ActiveBrain project40 demonstrated that aerobic exercise increased white matter in the brain, especially pertaining to the inferior fronto-ocular, inferior temporal, cingulate, middle occipital, and fusiform gyri regions of the brain, crucial for visual processing. Moreover, aerobic exercise has been shown to increase blood flow to the hippocampus.41 Even the manner and intensity of carrying out workouts are associated with memory and cognitive performance.42 Actively employing High-intensity interval training (HIIT) improves cognitive control and working memory in children aged 7 through 13.43 Most results are generalized to children due to the high plasticity and constant development of the brain that is undergone through their critical developmental period.43 However, that is not to say that adult brains cannot be improved from the same dietary improvements or exercise routines.

Intelligence also stems from activities. Factors that have been shown to improve intelligence in children include setting limits on screen time, increasing reading, encouraging questions, engaging in hands-on learning, incorporating mathematics into routines, and encouraging curiosity.44 In general, creating a stimulating environment that forces thinking and logic in a daily routine is encouraged, as it incorporates more brain regions.44 Humans should always strive to better their intelligence in all aspects of life and always seek truth through questioning everything. After all, intelligence is not a static process but a fluid concept that continuously grows, and although it may peak early on is still subject to refinements.

- Ziegler P. The Black Death. Harper & Row; 1971.

- Matthewson-Grand A. Life under lockdown. University of Cambridge Alumni. Published April 15, 2020. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.cam.ac.uk/alumni/life-in-lockdown

- Williams M. Chromatic Aberration. Universe Today. Published December 4, 2010. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.universetoday.com/articles/chromatic-aberration

- National Geographic Society. Isaac Newton: Who He Was, Why Apples Are Falling. National Geographic Education. Published December 6, 2017. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/isaac-newton-who-he-was-why-apples-are-falling/

- Ott T. Isaac Newton Changed the World While in Quarantine From the Plague. Biography.com. Published March 25, 2020. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.biography.com/scientists/isaac-newton-quarantine-plague-discoveries

- Nelkin D. Genome politics: An insider’s story. American Scientist. Published May–June 2004. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/genome-politics-an-insiders-story

- Newton’s ‘Principia’. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Published September 5, 2018. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/newton-principia/

- Bracco C. Einstein initiates the quantum age. CNRS News. Published June 5, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/1905-einstein-initiates-the-quantum-age

- Mozart Project. Mozart: A Prodigious Child Composer. Mozart Project. Published July 1, 2020. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.mozartproject.org/mozart-a-prodigious-child-composer/

- Sweeney M. Harry Bernstein, 101, author at age 96. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Published June 6, 2011. Accessed March 28, 2025. https://www.inquirer.com/philly/obituaries/20110606_Harry_Bernstein__101__author_at_age_96.html

- Plato’s Dualism: World of Forms and Sensible Things. Philosophy Institute. Accessed March 30, 2025. https://philosophy.institute/western-philosophy/platos-dualism-world-forms-sensible-things/.

- Zeiss CJ. Comparative milestones in rodent and human postnatal neurodevelopment: Implications for neurotoxicology. Toxicol Pathol. 2021;49(6):1049–1061. doi:10.1177/01926233211046933.

- Huttenlocher PR. Synaptic density in human frontal cortex—developmental changes and effects of aging. Brain Res. 1979;163(2):195-205. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(79)90349-4.

- Spear LP. Synaptic development in adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2 Suppl 2):S7–S13. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.006

- Deng Q, Wu C, Parker E, Liu TC, Duan R, Yang L. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: significance and summary of recent advances. Aging Dis. 2024;15(4):1537–1564. doi:10.14336/AD.2023.0907

- Singh S. Too many connections: How impaired synaptic pruning shapes the autistic brain. Women in Neuroscience UK. Published July 21, 2025. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.womeninneuroscienceuk.org/post/too-many-connections-how-impaired-synaptic-pruning-shapes-the-autistic-brain

- Bethlehem RAI, Seidlitz J, et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature. 2022;604:525-533. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04554-y.

- Grey Matter: What It Is & Function. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24831-grey-matter.

- van de Mortel LA, Thomas RM, van Wingen GA; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Grey matter loss at different stages of cognitive decline: A role for the thalamus in developing Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;83(2):705–720. doi:10.3233/JAD-210173. PMCID: PMC8543264.

- Ruhl C. What Is Intelligence in Psychology? Simply Psychology. February 1, 2024. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.simplypsychology.org/intelligence.html

- Lewis Terman. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lewis-Terman

- Gardner H. Multiple Intelligences Are Not Learning Styles. Harvard Graduate School of Education. Published October 2013. Accessed April 12, 2025. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/news/13/10/multiple-intelligences-are-not-learning-styles

- Hill WD, Marioni RE, Maghzian O, et al. A combined analysis of genetically correlated traits identifies 187 loci and a role for neurogenesis and myelination in intelligence. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:169-181. doi:10.1038/s41380-017-0001-5

- GeneusDNA. DNA and Intelligence: Is Your Child’s IQ Inherited from Parents? GeneusDNA website. Published January 9, 2025. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.geneusdna.com/en-iq/blog/dna-intelligence

- Hill WD, Arslan RC, Xia C, et al. Genomic analysis of family data reveals additional genetic effects on intelligence and personality. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:2347-2362. doi:10.1038/s41380-017-0005-1

- Childhood Intelligence Is Heritable, Highly Polygenic and Associated With FNBP1L. PubMed. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23358156/

- Ruthsatz J, Urbach JB. Child prodigy: A novel cognitive profile places elevated general intelligence, exceptional working memory and attention to detail at the root of prodigiousness. Intelligence. 2012;40(5):419-426. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2012.06.002

- Gil-Espinosa FJ, Chillón P, Fernández-García JC, Cadenas-Sánchez C. Association of Physical Fitness with Intelligence and Academic Achievement in Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(12):4362. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124362. PMCID: PMC7344740.

- Mandolesi L, Polverino A, Montuori S, et al. Effects of Physical Exercise on Cognitive Functioning and Wellbeing: Biological and Psychological Benefits. Front Psychol. 2018;9:509. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00509

- Stillman CM, Esteban-Cornejo I, Brown B, et al. Effects of Exercise on Brain and Cognition Across Age Groups and Health States. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43(7):533-543. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2020.04.010

- Mergenthaler P, Lindauer U, Dienel GA, Meisel A. Sugar for the Brain: The Role of Glucose in Physiological and Pathological Brain Function. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(10):587-597. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2013.07.001

- Gillespie KM, White MJ, Kemps E, Moore H. The Impact of Free and Added Sugars on Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023;16(1):75. doi:10.3390/nu16010075

- Theola J, Andriastuti M. Neurodevelopmental Impairments as Long-term Effects of Iron Deficiency in Early Childhood: A Systematic Review. Balkan Med J. 2025;42(2):108-120. doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2025.2024-11-24

- Stringham JM, Johnson EJ, Hammond BR. Lutein across the lifespan: From childhood cognitive performance to the aging eye and brain. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(7):nzz066. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzz066. PMCID: PMC6629295.

- Laus MF, Vales LDMF, Costa TMB, Almeida SS. Early postnatal protein-calorie malnutrition and cognition: A review of human and animal studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(2):590–612. doi:10.3390/ijerph8020590. PMCID: PMC3084481.

- Jirout J, LoCasale-Crouch J, Turnbull K, et al. How lifestyle factors affect cognitive and executive function and the ability to learn in children. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1953. doi:10.3390/nu11081953.

- Gómez-Pinilla F. Brain health across the lifespan: A systematic review on the role of omega-3 fatty acid supplements. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1094. doi:10.3390/nu10081094.

- Chaddock-Heyman L, Erickson KI, Chappell MA, et al. Aerobic fitness is associated with greater hippocampal cerebral blood flow in children. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016;20:52–58. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2016.07.001. PMCID: PMC6987716.

- Chaddock L, Erickson KI, Prakash RS, et al. Basal Ganglia Volume Is Associated With Aerobic Fitness in Preadolescent Children. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32(3):249-256. doi:10.1159/000316648

- Clark CM, Guadagni V, Mazerolle EL, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on white matter microstructure in the aging brain. Behav Brain Res. 2019;373:112042. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112042.

- Kaufman CS, Honea RA, Pleen J, Lepping RJ. Aerobic Exercise Improves Hippocampal Blood Flow for Hypertensive Apolipoprotein E4 Carriers. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(8):2026-2037. doi:10.1177/0271678X21990342

- How Workouts May Impact Your Memory. Dartmouth News. Published September 29, 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://home.dartmouth.edu/news/2022/09/how-workouts-may-impact-your-memory

- Alves AR, Dias R, et al. High-Intensity Interval Training Upon Cognitive and Psychological Outcomes in Youth: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5344. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105344

- Nobre JNP, Morais RLS, Viñola Prat B, et al. Environmental opportunities facilitating cognitive development in preschoolers: development of a multicriteria index. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2023;130(1):65–76. doi:10.1007/s00702-022-02568-4. PMCID: PMC9676873.